by Jamie Dobson and Pini Reznik

In our last book, Cloud Native Transformation, we learnt about Jenny and WealthGrid. WealthGrid is a midsize firm which, on its third attempt, got its Cloud Native transformation right. Jenny had learnt a lot on the way, including the following:

Since helping WealthGrid to succeed with Cloud Native, Jenny was promoted to the management team. She is now directly responsible for strategy. And it was going well until: another stranger came to town.

"All great literature is one of two stories; a man goes on a journey or a stranger comes to town."

Leo Tolstoy

Recently, the margins on WealthGrid’s core services have started to erode. At first Jenny and her colleagues on the management team put this down to seasonal behaviour. Who was worried about fluctuations in the summer months? At the same time, there was a rise in requests from their customers for services that WealthGrid didn’t provide. Jenny and her team brushed that off as moaning customers. Who didn’t have a handful of them?

Jenny was about to learn an important rule of thumb. The two surest signs that the landscape is changing are eroding margins and customers who are becoming more demanding. These two signals, when they come together, indicate that a company is beginning to lose or has already lost its relevance. Any company who stays on this trajectory won’t last much longer.

After a period of denial, the management team at WealthGrid realised that three related shifts had occurred at the same time.

Together, these three shifts created a perfect storm for WealthGrid; they are left in a situation where they have to help their own disgruntled customers migrate to their competitors.

The perfect storm catapults Jenny and her colleagues into what Andy Grove, former CEO of Intel, called ‘the valley of death’. In the valley, things are tense. People lose faith in their leaders. Leaders lose faith in themselves. Members of the management team blame each other. This infighting is driven because, for the time being, the ship is rudderless. Different managers think the company should go in different directions.

At WealthGrid, some managers think they should re-double their efforts in the personal wealth-management space. They are in denial of their shrinking margins and think that advertising will return them to growth. Other managers think that trimming their service to target only a tiny subset of their current users will give them more ‘marketing bang for their buck’. Some of the engineering managers have no clue why the others are talking about marketing at all and instead want to create new digital products to compete head on with the new upstarts.

After a while, Jenny starts to think she can see the future. She doesn't think she should trim WealthGrid’s service, targeting only one type of customer. Nor does she think competing, feature for feature, with the upstarts is wise. She instead wants to understand the needs that these upstarts are serving.

Therefore, after a period of infighting, Jenny starts to imagine a new future. She starts to voice this, and that is enough for her team to start to think about a few simple steps. Jenny is using the Vision First pattern.

When we are in the valley of death, you don’t need a plan, you need to move. Actions move you along, letting you learn as you go. These moves lead you to new moves, ones you could not have possibly seen before. If none of the possible new moves take you to a better place, you can backtrack and start again.

The next step for Jenny and her team is to take such actions. These could be a series of prototypes to try and understand the behaviour of the users who have been migrating from their platform. However, they could also be less expensive than this, and simply involve talking to users. For this, Jenny can use the Exploratory Experiment or Research Through Action patterns. The point is that Jenny and her team are trying to gather information as cheaply as possible in order to inform future decisions. They cannot afford to wait for this information to come to them.

|

|

Andrew S. Grove, Only The Paranoid Survive: How to Exploit the Crisis Points that Challenge Every Company, (Random House, 1988), p. 146.

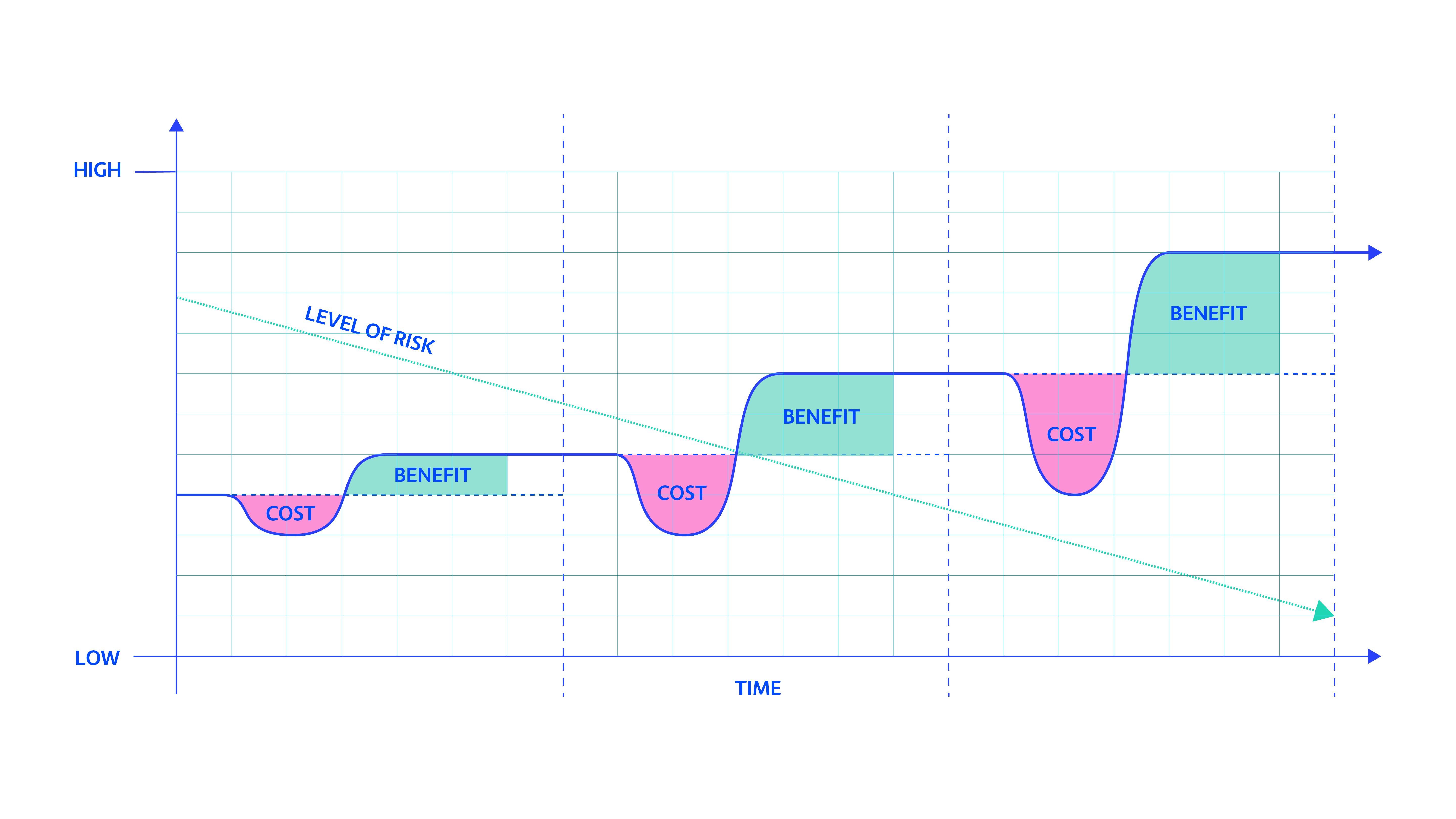

The mistakes that most companies make then it comes to strategy is that they go too big too early. This is a waste of money, which is bad enough, but mainly it’s a waste of energy, the one thing you don’t have when you're in the valley of death; marshalling all your resources only to squander them on a fantasy will leave you even more demoralised. Instead, we think of strategic actions as existing on a scale. On one end we have No Regret Moves and on the other Big Bets. In between are Options and Hedges. Typically, we move on this scale from left to right.

Other no regret moves include learning, speaking to people and whiteboarding. This is because the goal, when surrounded by uncertainty, is to create as much situational awareness as possible. It is situational awareness that drives better decisions and creates hypotheses that we can later test.

A Proof of Concept is a typical option; it’s going to cost something. This is a given and an example of a ‘strategy tax’. However, if the PoC works, then we have found a way to serve our users needs. If it doesn’t work, we have disqualified one option and we can try again.

When we think about moves in terms of no regrets, options and bets, what are we actually doing? We are focussed on knowledge generation. This is because knowledge is the antidote to risk.

In the beginning, when risk and uncertainty are high, and knowledge is low, we use the No Regret Moves pattern to slowly increase knowledge and therefore reduce uncertainty. As we get more confident, we can start to spend more energy on options. As each option is executed, certainty is increased and risk is further decreased. The quicker you execute these options, the quicker you learn.

At some point, as risk tends towards zero, you can make much bigger bets. All through the process, benefits are accruing and, as the bets get bigger, so too do the benefits.

When it comes to strategic actions, there are two classic errors. The first is to move too quickly. The second is to not move at all. Because uncertainty is so psychologically uncomfortable, people want to get out of it as soon as possible. In order to do this, they move as quickly as possible, often forgetting No Regret Moves and Options all together and jumping straight into Big Bets.

The psychologically discomfort manifests itself, often, with bullishness and bravado. This is what Jenny has to deal with. She reminds her colleagues that their previously rash decisions had led to expensive misfires and embarrassing U-turns.

The second error is to focus entirely on no regret moves. No regret moves are seductive because they are always valuable and cost very little. But you cannot leave the valley of death making only No Regret Moves. Jenny and her team needed a radical breakthrough, not incremental improvements.

When it comes to strategic actions, one type of manager might want to get to a Big Bet as soon as possible. Another might be too terrified to even start. Neither approach will work. The secret to succeed with a Gradually Raising the Stakes pattern lies in the word ‘gradually’. This, however, requires that we get comfortable with risk, moving beyond No Regret Moves, and mustering the courage to face potential disappointment.

Remembering her experiences with WealthGrid’s previous Cloud Native transformation, Jenny goes to the white board and draws this:

You can gradually reduce risk over time with ever more elaborate moves.

You can gradually reduce risk over time with ever more elaborate moves.

Jenny explains that as a team, they want to get to the big bet on the right as quickly as possible. She explains that they should only do that once the team has stacked the odds in their favour, using options, which are in the middle of the graph. Finally, she says, the only way to find out a sensible range of options is to make a few no regret moves.

Whilst at the whiteboard, Jenny reminds the team that, at WealthGrid, people don’t get punished for taking risks. She scrawls that in big letters. Underneath that, she writes, “get comfortable with being uncomfortable”. Jenny knows that if her team can’t deal with the anguish of uncertainty, their strategy will suffer.

In the end, Jenny and the team at WealthGrid managed to beat their competitors and navigate their ‘perfect storm’. Like all teams, they had been in the valley of death long before they realised it let alone could accept it. They were in denial, which was why they ignored their eroding margins and demanding customers. Then they started to fight, second guessing each other and themselves.

However, at one moment they started to see what the future might look like. They then used the Gradually Raising the Stakes pattern. This allowed them to build up to a big bet, which was a new application that served the underlying needs of their younger users whilst having the back-end systems that let them adhere to the extra regulatory requirements placed upon them.

WealthGrid was able to use one, essential, pattern. They used Reduce Cost of Experimentation. If you frame strategy as an emerging process, one in which you can stack the odds of success in your favour through experimentation, then you need a system for experimentation. Many organisations don’t have this; there are no low-cost ways to test an idea.

Previously, WealthGrid had adopted Cloud Native. Cloud Native is, simply stated, a framework for rapidly developing products. It’s not only a technical paradigm, using technologies like containers and dynamic orchestrators, such as Kubernetes. Rather, it is a sociotechnology, encompassing processes that enable experimentation, such as A:B testing and build automation, and processes that enable learning on the fly, such as blameless inquiry. Underpinning all of this is psychological safety. No psychological safety, no Cloud Native.

When we make strategy too formulaic we render it useless. If, however, we have no framework in which to operate, then we spin our wheels trying to learn everything as we go. Patterns link the knowledge of experts to the manager on the street. As we saw with Jenny, they help you with your thinking but won’t do it for you.

The patterns work best when viewed as part of a learning process. We think of strategy as an emergent property that arises from the interaction between actions and the environment in which we take them. There is room for thought but we accept as we try to shape the environment, it shapes us too. The way to learn is through strategic actions. When it comes to strategic actions , for psychological reasons, people tend to be too bullish, jumping to big bets and ‘getting it over with’ as quickly as possible. Or

they are too sheepish, lingering in no-regret moves, which never get you out of the valley of death. The trick here is to recognise these two modes whilst understanding that we can systematically reduce risk by gradually raising the stakes.

Our final thought is this: Strategy is about risk and therefore involves damaged reputations, broken relationships, financial losses, tears, tantrums, and tiffs. The patterns in this book can limit the damage but only we can take the first step, meeting life on its terms, and hopefully prospering in the process.

Check out the rest of the Container Solutions blogs:

How To Implement Psychological Safety in a Time of Crisis

by Andrea Dobson-Kock

How to Manage Your Business in a Crisis

by Pini Reznik

How to Manage Distributed Teams (Even When You Have No Choice)

by Michael Müller